As medical education continues to evolve toward competency-based models, Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) are emerging as a powerful bridge between abstract competencies and real-world clinical practice. EPAs offer a practical and observable framework that supports learners’ development toward independent responsibility. But how do you actually design clear and effective EPAs? In this article, we’ll walk you through the essential elements of EPA design, using practical examples and best practices to help you get started.

What is an EPA?

An Entrustable Professional Activity (EPA) is a key activity in professional practice that can be entrusted to a trainee once sufficient competence has been demonstrated. Unlike traditional competencies, which are often abstract and difficult to assess in practice, EPAs are grounded in day-to-day clinical responsibilities. Think of them as the answer to the question: “Is this trainee ready to take on real clinical responsibility?”

A well-designed EPA allows trainers to make meaningful decisions about learner readiness, while giving trainees a clear and structured path to independent practice.

Criteria for a well-designed EPA

A well-designed EPA consists of several essential components. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

1. Entrustability and scope

The EPA must describe a activity that is entrustable: something that a trainer can realistically assign to a trainee for independent execution. It should be clearly defined and fall within the scope of real-world responsibilities. Avoid vague terms like “medical knowledge” or “professionalism”. These are competencies, not entrustable activities.

Instead, focus on specific tasks. For example:

Not good enough: “Demonstrate professionalism”

Well done: “Diagnose and treat a patient with asthma”

The scope should be broad enough to avoid micromanagement, yet narrow enough to remain meaningful and assessable.

2. Practical situation

Each EPA should specify the context in which it applies. This ensures clarity and consistency during assessment. In our asthma example, this could be:

“Diagnosing and treating a patient with asthma in a primary care setting.”

This helps align expectations for both trainees and assessors and ensures the EPA reflects actual clinical practice.

3. Required knowledge, skills, and attitudes

Clearly listing what a trainee needs to know and be able to do is essential for both teaching and assessment. These should be broken down as follows:

- Knowledge: The essential knowledge required to perform the EPA. e.g., Asthma pathophysiology, treatment guidelines, medication classes, patient education strategies.

- Skills:The essential skills that a learner should be able to perform to master this EPA. e.g., Taking patient history, performing physical exams, interpreting spirometry results, developing treatment plans.

- Attitudes: The attitudes that a learner should display while carrying out this EPA. e.g., Showing empathy, involving patients in decision-making, collaborating respectfully with colleagues.

4. Assessment strategy

To ensure a structured and objective evaluation, each EPA should define how and with which tools progress will be assessed. Common tools include:

- Workplace-Based Assessments (WBA)

- Case-Based Discussions (CBD)

- Patient Simulations

- Patient Feedback Forms

These assessments, especially when used formatively, build the foundation for a summative entrustment decision made by multiple observers.

Example: EPA for asthma care

Let’s summarize the process with a practical example:

EPA Title: Diagnosing and treating a patient with asthma

Context: In a primary care setting

Knowledge:

- Pathophysiology of asthma

- National treatment guidelines

- Medication mechanisms and side effects

- Patient education approaches

Skills:

- History-taking and physical examination

- Spirometry interpretation

- Shared decision-making

- Treatment planning

Attitudes:

- Empathy and active listening

- Patient-centered care

- Respect for team collaboration

Assessment tools:

- Workplace-Based Assessments

- Patient simulations

- Case-Based Discussions

- Structured patient feedback

All together, these components takes competencies and turns them into real, visible activities that we can actually observe in practice.

In addition, by outlining what tools are needed to effectively assess progress, we make sure the evaluation of EPA’s is structured and fair.

Final Thoughts

Designing EPAs takes practice, collaboration, and a clear understanding of clinical responsibilities. When done right, EPAs can significantly improve the clarity, transparency, and effectiveness of medical training. They empower both trainers and trainees with a structured, practical way to translate competencies into daily practice. By clearly defining EPAs, you lay the foundation for better education, safer practice, and more confident healthcare professionals.

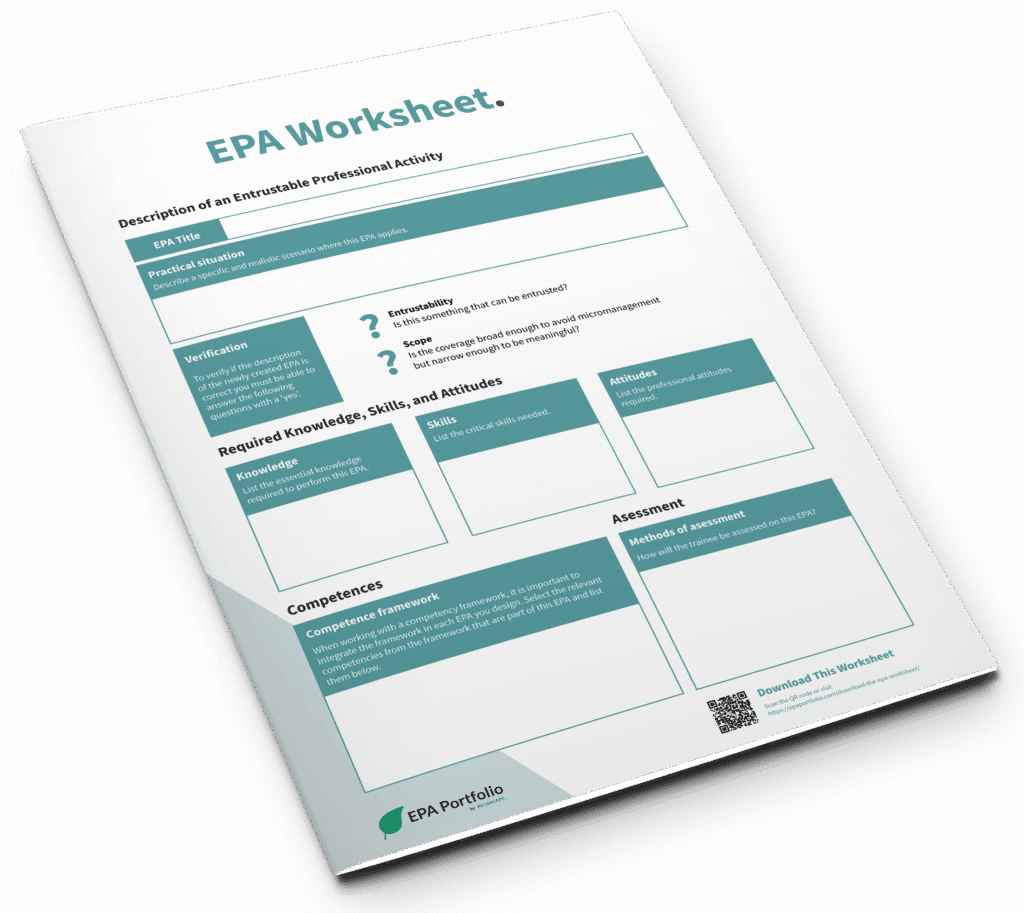

Download our EPA worksheet

To help you get started, we’ve developed an EPA Worksheet, a practical tool that guides you through the steps of EPA design. Feel free to use the worksheet as a team activity or simply as a way to kickstart your own design. Simply fill out the form below, and we’ll send it directly to your inbox!

For all other articles and webinars, visit our EPA learning hub!